(Born July 3, 1907 in Berlin, Germany; died November 15, 2000 in White Bear Lake, Minnesota)

(Born July 3, 1907 in Berlin, Germany; died November 15, 2000 in White Bear Lake, Minnesota)

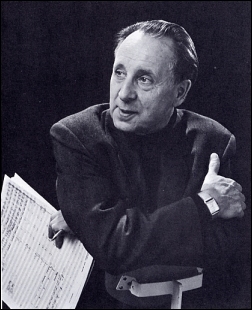

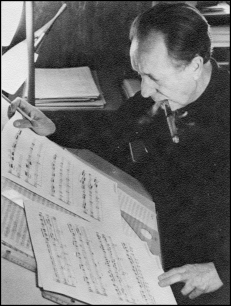

Gene Gutchë's primary allegiance was to his own independence. He chose to work in the tranquil isolation of a home midst giant old trees a few paces from the shores of White Bear Lake. Though he earned a Ph.D. in composition at the University of Iowa in 1953, Gutchë did not enter the academic portals that might have opened to him. He later explained his rejection of the dual role filled by most American composers: "Even in his most precocious achievement the Academic Artist cannot of necessity create and teach at the same time. The teacher is as much artist as the artist. Complete expression is a complete surrender to an idea. The ultimate desire is to fire the imagination, to express an idea for its own sake."

With Gutchë's choice came total obscurity for some years as well as detachment from his colleagues. But Gutchë has not been a hermit, for his scores, like his peppery essays, reveal a sincere commitment to audience and performer: "Art can only exist among people for whom it is deliberately intended," he concluded in an essay scornful of taste seduced by the merely new or bizarre ("Pandora's Music box: Estrangement between Public and Contemporary Music"). For Gutchë, a composer's music is not to be so much an expression of himself as "an image of what we are."

The philosophy that music must create images of human experience rather than wander through the "calculus forests" of technique for its own sake, suggests the influence of a great teacher, Donald Ferguson. Ferguson described the student who had approached him in the late '20s -- "bewildered, untrained, and uncertain of everything but his consuming desire to compose. . . . I did what I could. He disappeared for several years, returned (sadder, wiser, and more determined than ever), and enrolled in the music department at the University. Mr. Aliferis in composition and I in basic theory and history did something, I suppose, to shape his musical thought."

Ferguson concluded: "I suspect that we shall one day find him an important figure." Not many years after that Gutchë began to be discovered by conductors, so that his works have been widely performed and recorded.

Gutchë was born in Berlin, son of a successful fruit importer from Alsace-Lorraine, hence the French name. His mother, of Polish descent, betrayed a wildly Romantic imagination when she named her only child Romeo Maximilian Eugene Ludwig Gutschë. The composer dropped the "s" from his surname (easier to pronounce this way) and preferred to be known simply as Gene. Educated in schools in Italy, Switzerland and Germany, he was something of a runaway when he boarded a boat for America at age eighteen. His destination: Texas, lured by its Wild West associations. Though he knew five languages, the immigrant couldn't speak a work of English. When the $500 his father had given him disappeared, he found work on a ranch shocking wheat, following the wheatfields north. He came to St. Paul because an uncle was associated with the Archdiocese; upon arriving, he found that the priest had been transferred to Canada. Gutchë stayed, however, beginning the musical studies that his businessman father had deprived him of in Europe. Apart from some early piano lessons, he was entirely American-trained.

During the Depression, newly married, Gutchë abandoned his University studies to try the export business on the East Coast. But the outbreak of war curtailed his business. No longer young -- already 35 -- he returned to Minnesota to resume his musical path, completing an M.A. degree at the University of Minnesota, followed three years later by a doctorate from the University of Iowa under P.G. Clapp. The proximity of the Minnesota Orchestra during its Northrop residence was significant in Gutchë's education: he credited Dmitri Mitropoulos with opening the door to him for rehearsals, and the players for patiently answering his questions about their instruments as he learned to orchestrate.

During the Depression, newly married, Gutchë abandoned his University studies to try the export business on the East Coast. But the outbreak of war curtailed his business. No longer young -- already 35 -- he returned to Minnesota to resume his musical path, completing an M.A. degree at the University of Minnesota, followed three years later by a doctorate from the University of Iowa under P.G. Clapp. The proximity of the Minnesota Orchestra during its Northrop residence was significant in Gutchë's education: he credited Dmitri Mitropoulos with opening the door to him for rehearsals, and the players for patiently answering his questions about their instruments as he learned to orchestrate.

When Gutchë got down to the business of composing, his productivity was virtually non-stop. In an age in which the orchestra has become essentially a museum of the past, Gutchë's vivid scores have gradually taken root. His work does not demand outlandish stunts from the players nor forbearance from the listeners. Many of his works are programmatic, such as Hsiang Fei , Holofernes, Genghis Khan, Epimetheus USA. Gutchë believed that almost any sound is tolerated when a program lends stimulus to the event. There is irony in Gutchë's admiration of Schoenberg, for though the Gutchë idiom (atonal, dissonant, yet lyric) would not have been possible without the 12-tone revolution that destroyed the old system, his own scores -- including Bi-Centurion -- do not necessarily convey dodecaphonic impressions. He took from the new what he wanted, never severing his art from the past. Propulsive rhythms, intensity of expression -- these are the hallmarks of Gutchë's language. Of Schoenberg, who gave him great encouragement, he wrote: "It produced one genius to put our house in readiness for what is to be the new Ictus in music."

Four string quartets aside, Gutchë amassed a host of orchestral works, with no fewer than six symphonies. The Fifth Symphony for Strings won the 1962 Oscar Esplà International Composition Award and was subsequently broadcast and televised nationwide. He composed several concertos, for the more conventional media of piano, violin and cello, as well as a Timpani Concertante. For The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra he composed Bongo Divertimento, also available in a version for large orchestra; the work has been performed by the Münchner Philharmoniker.

In 1977, Gutchë completed his Opus 50: Perseus and Andromeda XX, commissioned by the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. Thomas Schippers who was to have conducted the World Première in Cincinnati's Music Hall, and conclude his Orchestra's midwinter tour with a Carnegie Hall performance, dying of cancer, had to be replaced with Kenneth Schermerhorn of the Milwaukee Symphony as Guest Conductor. Two weeks later the American Symphony offered the New York première of Gutchë's Icarus, commissioned by the National Symphony Orchestra.

David Zinman, who commissioned Gutchë's Bi-Centurion for the Rochester Philharmonic New York, did the première performances in January 1977. The following spring, Zinman presented Icarus in the Eastman Theater and after an extensive tour recorded the work for VOX Turnabout as part of the Ford Foundation Recording-Publishing Program.

Gutchë added two new commissions for the 1978/79 seasons: Akhenaten, Opus 51, for the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Kenneth Schermerhorn, and Helios Kinetic, Opus 52, for the Florida Philharmonic with Brian Priestman. That season he also received a National Endowment for the Arts Grant for the third time.

Unlike the majority of his colleagues, Gutchë was not interested in conducting or teaching and devoted all of his time and energy to composing. He probably enjoyed his greatest success in the 1960s and 1970s; during this span there would be as many as 60 performances of his works per year around the country. All told, he composed thirteen programmatic works, along with six symphonies, five concertos, and numerous pieces for chorus and chamber ensemble. He also wrote a number of articles for music journals and published a book of essays entitled Come Prima in 1970.

Gutchë died of natural causes in 2000 at the age of 93.

Born in Berlin, Germany on July 3, 1907 as Romeo Maximilian Eugene Ludwig Gutschë, young Gene received little musical encouragement from his parents. At age 18 and with $500 in his pocket, he left his family and boarded a boat for America. There, working his way northward as a migrant farmer, he was finally able to train in music composition at the University of Minnesota (MA, 1950) and the University of Iowa (PhD, 1953). Best known for his orchestral repertoire, which includes six symphonies and numerous programmatic works, Gene Gutchë's catalog also includes four string quartets, five concerti, and numerous smaller works for chamber ensembles. His music, performed nationally and internationally, was commissioned by the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Florida Philharmonic, Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra, National Symphony Orchestra, Rochester Philharmonic, and The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, among others. His awards include the Minnesota State Centennial Prize, the Oscar Espla International Composition Award, two Guggenheim Fellowships, and four grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. He died in White Bear Lake, Minnesota, in 2000.

Born in Berlin, Germany on July 3, 1907 as Romeo Maximilian Eugene Ludwig Gutschë, young Gene received little musical encouragement from his parents. At age 18 and with $500 in his pocket, he left his family and boarded a boat for America. There, working his way northward as a migrant farmer, he was finally able to train in music composition at the University of Minnesota (MA, 1950) and the University of Iowa (PhD, 1953). Best known for his orchestral repertoire, which includes six symphonies and numerous programmatic works, Gene Gutchë's catalog also includes four string quartets, five concerti, and numerous smaller works for chamber ensembles. His music, performed nationally and internationally, was commissioned by the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Florida Philharmonic, Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra, National Symphony Orchestra, Rochester Philharmonic, and The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, among others. His awards include the Minnesota State Centennial Prize, the Oscar Espla International Composition Award, two Guggenheim Fellowships, and four grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. He died in White Bear Lake, Minnesota, in 2000.

Though writing in an atonal idiom, Gutchë's music was not typical of his time. Called "refreshing" (New York Times, 1964), "unusually attractive" (St. Paul Pioneer Press), and "highly individual" (Music Courier), Gutchë's vivid music is often imbued with lyricism, romance, and a healthy dose of humor.

Gutchë's complete orchestral scores are available through the Fleisher Collection, and his chamber works are available from The Schubert Club.